I began writing about Motovun and Istria two months ago. I kept coming back to this, picking at it, or reading it and trying to find the right mood so I could wrangle the right words. Never have I wanted to “get a place right” as much as I wanted to do Motovun and Istria justice. I hope now that I have achieved that. Maybe it’s an impossible task. Maybe some places defy “getting it right”.

Motovun seems a lifetime ago. A video appeared in my Facebook feed tonight, leaving me with strange mingling of pride, love, and longing.

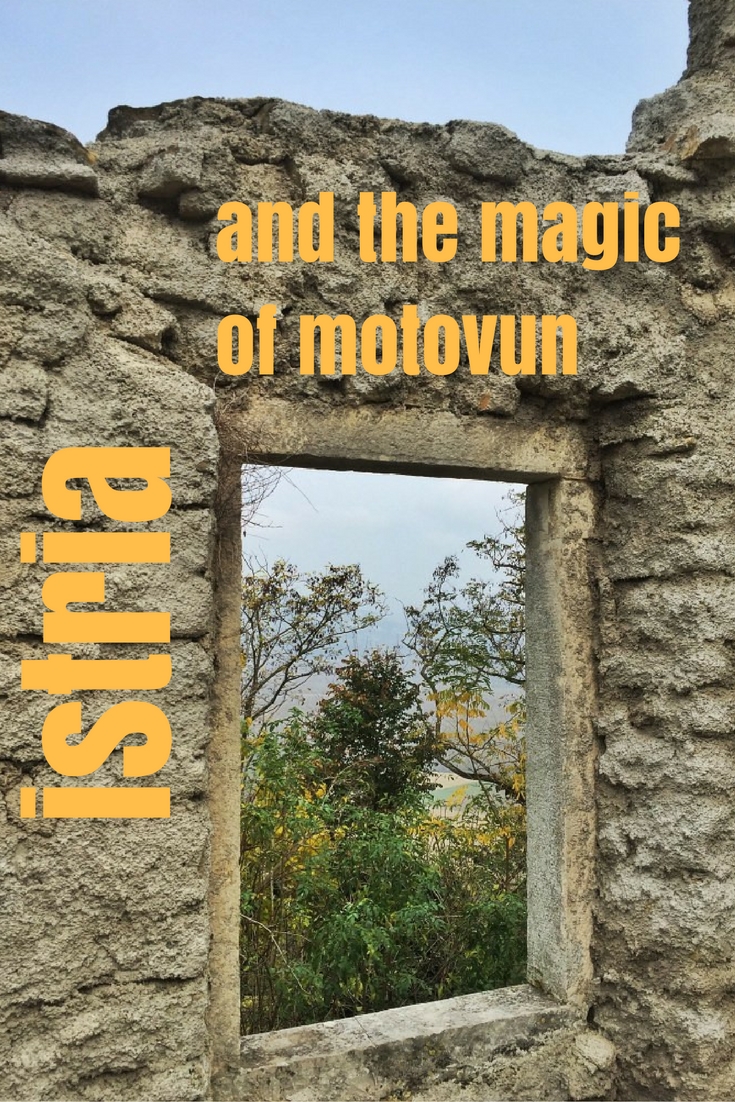

I haven’t written much about Motovun because words have yet to be invented for describing it. Magical, otherworldly, idyllic – all these are true but also trite and overused. They feel understated and cheap when it comes to describing such a cherished spot.

I’ve found things to love about every country I’ve seen, but one place that calls me back the strongest is Croatia. Istria stole my heart and left me fumbling for words.

A land seemingly forgotten by time, site of a massive exodus after the Second World War, Istria is described by its own government as a “hinterland;” filled with agriculture and forest but little else. Its towns all have population in the thousands, few make “tens of thousands.” One is the “smallest town in the world,” Hum, with a whopping 17 citizens.

My friend Alen points at Glagolitic script in the smallest town in the world, Hum. This is an ancient writing used only in Great Moravia, Bulgaria, and last kept alive by the Croats.

The Not-So-New World

The landscape is littered with abandoned ruins. Crumbling stone cottages consumed by nature, derelict buildings, overgrown land. All the sad results of 300,000 people leaving in under 20 years.

Istria sprawls into Slovenia and Italy too, but 70% belongs to Croatia. Once it was all Italian. But it was Yugoslavian before that. And Austrian, and Venetian, and…

If Istria’s history was a Facebook “relationship” status, it’d be “it’s complicated.”

Perhaps part of the magic of Istria for me is just how much its history baffles me. Last fall, a condescending reader mocked me for my inability to grasp what seems like countless handovers of the region in centuries past. But I come from a country that had one war and things got decided then and stayed decided. My home city? A paltry 130 years old.

So, no, I don’t understand the complexity of the Istrian history. I’m not sure I ever will.

Istria’s Motovun in autumn. I was in an apartment on the top left just above the wall.

So, the Dummies guide to “Basic Istria,” then?

Okay, so as best I can make it out from internet cheat sheets, this is kinda how the last 2,000 years went for Istria.

From 178 BC, Istria was controlled by Rome. This explains how I came to be standing in a 2,000-year-old Roman Coliseum all alone in Pula, Croatia, on one windy November day.

Some 600 years later it fell to the Ostrogoths, who summarily had their asses handed to them by the Byzantines just 50 years later, in 538. This led to 250 years of tumultuous times in which several “landlords” took Istria under their fold.

Enter the Frankish Kingdom, who ran the “Istria” show starting in 789 for the next three centuries, when things began shaking up. By 1145, Venice was kicking ass and taking names. Over the next two centuries, Venice pretty much took control of the entire Venetian peninsula. This map gives a good perspective on how much Venice ruled then. They’d retain their sprawling empire for nearly 400 years, when Napoleon would defeat the Venetians in 1797. He then traded Istria for control of the Netherlands and Lombardia. Thus began the Austrian age in Istria.

These walls are 1,000 years old. And this summit has never been breached. Motovun may have changed hands, but it was never conquered. Not once.

Modern-ish Istria 101

That’d continue for just over a century, until the First World War heralded the demise of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Italy was then given control of Istria, despite nationalistic grumblings by ethnic Croatians for the previous half-century and beyond. This Croat patriotism became particularly vexing as the rise of Fascism in Italy introduced “forced Italianism” in Istria. People with Croat language, names, or culture were forced to assimilate to Italian ways.

When Mussolini got crushed in the Second World War, Yugoslavians rose up with fierce nationalism. This is when Tito and “the Partisans” occupied all of Istria. Fascists got the boot and “liberation” was the order of the day. Sadly, this meant a swinging of the pendulum, and the cultural bullying felt by Croatians under the Italians was soon visited upon the remaining Italians in Istria.

Massacres unfolded too. Historians still bicker about the number, which ranges from “hundreds” of Istrian Italians slaughtered to over 20,000. Beyond that was intimidation and manipulation, which ultimately inspired somewhere between 250,000 to 330,000 Istrian Italians to flee across the border to Italy proper.

Istrian was then Yugoslavian until revolution brought about the end of Yugoslavia in 1991. Since 1995, it has been largely Croatian. Italy and Slovenia still possess 30% of Istria between them.

When I write of Istria in this post, though, I speak entirely of Croatia’s Istria.

Clear as mud, right?

The hillside on Motovun in autumn. These homes are as old as 800 years old, some of them.

“If the Walls Could Talk”

So… You see how I might have been a bit confused about things when I was reading the non-Dummies “complicated and name-y-name-name” version of Istrian history. Packed with so much information, my head wanted to explode.

Long before I left Canada, talking with a friend, we spoke of the “living history” aspect of life in Europe. As outsiders, we romanticize history. We walk the streets and feel as though the walls tell stories of wistful ages past. For Europeans, though, the history isn’t long gone. For some, memories of wet blood still drips down those walls.

After the Brexit vote this June, there was much talk of how this was Europe’s longest peace since the Fall of Rome – the 70-some years since World War Two ended. But for those in the Balkans, this is untrue. Their wars ended only 20 years ago and simmering discontent is evident to anyone who stays a while. Some locals went to tears in talking of the wars. Others want to move past it and feel it’s just another chapter in a long history of strife between warring Croats and Serbs of ancient times.

Uneasy Silences

So today, Croatia’s Istria is a region hard to pinpoint. There’s a sadness that seems omnipresent for me. Wounds too fresh that have yet to close. A land torn asunder from wars. Old neighbours gone, after a half-century of back-and-forth identity suppression and ethnic cleansing, under not only different national leaders, but invading forces too.

The idyllic peace I found on my Istrian hilltop seems ironic once one closes their eyes and imagines everything from Napoleon’s forces to invading Serbs. Those horizons have seen their share of spilt blood in centuries past. I can’t help but wonder if that peace will last my lifetime.

Every day I saw a sunrise or sunset that was a variation on this. It left me with deep gratitude every single time.

Idyll Deception

But peace was what I saw when I stumbled upon a photo of Motovun, a gorgeous mountain town shrouded in fog. Closing my eyes, I felt I was there. Surrounded by history and forests and magical light.

On November 1, 2015, I made it so.

A loft atop Motovun became home for four weeks. It was hard on my out-of-shape body. I’d park 300 metres down and make the brutal walk up 500-year-old cobblestones. The stony road dipped and rose, betraying deep impressions made over a century with motor vehicles rumbling uphill and horse-drawn carts before that.

The idea of thriving on that remote hilltop a thousand years ago boggled my mind. Even today, life is hard in Motovun. Getting to neighbouring towns is an ordeal. 20, 30 minutes by car through winding valley passes. Many are hilltop towns themselves.

Still, once that fog rolls in and blankets the valley, it’s a wistful, mystical world. The fog fortuitously makes the region’s truffles and wine a claim to fame for Istria today. Its bounty summons foodies from around the world.

That fog’s weighty, moody presence coupled with the rich cuisine it sustains is all part of the Istrian irony. Always a hard and complex life, it is richly enjoyed, though oftentimes endured too, by those who still call it home.

My last sunrise in Istria defied description. This was the morning fog that frequently greeted me. I was spellbound by it.

Identity Intrigue in Istria

In the land that time forgot, even the ethnic cleansing of the past remains in the past. Today, Istria is all things. It is Croatian. It is Italian. Most of all, it is Istrian.

Many locals speak both Italian and Croatian, even German, as a throwback to the Austrian landlords ousted post-World War I.

Explore eateries and you will find schnitzel, handmade pasta, and Balkan delights like burek (a phyllo pastry filled with farmer’s fresh soft, unripened cheese). All are testimony to the cultural crossroads that define Istria. Things which belong in surrounding countries are at home here, too. Like manestre, the Istrian version of minestrone, a hearty soup that became my mainstay there.

Istria, because of recent socialist history under a dictator, felt like an awkward teenager. So conscious of its recent struggles is it that it almost fails to realize how much it has to offer. I felt sort of like Croatia’s Istria was “Jan Brady” to Tuscany’s “Marcia”. They’re so similar that it’s only when you compare them side by side that you realize the differences. Italy, Italy, Italy!

Istria’s shortcoming is that it doesn’t realize how incredible it is. That shortcoming is a selling point. It’s charming and budget-friendly, with sometimes haphazardly labelled wine and underpriced meals. Once they embrace more marketing and finesse, prices will skyrocket, and the place I saw will be a distant memory. But it will one day realize its potential and strive to achieve that. Its people deserve to benefit from all Istria offers.

Looks simplistic, and Italian, but polenta is as Istrian as anything, and these white truffles are among the best in the world, and, paired with Istrian Malvasia wine, this is a meal I will remember forever.

A Modern Nomad’s Life in the Old World

My Istrian life constituted largely of rolling from bed to incredible sunrises spilling over the fog-covered valley. Every morning I’d marvel as Louis Armstrong once did, how wonderful this world can be.

I’d dress and wander to a shop just a hundred paces from my door, while guardedly navigating cobblestones. Smiling, I’d say “Dobro jutro” to staff before buying a spinach-and-cheese burek for home. I’d amble back to my apartment, stealing a moment’s glimpse between stone fences to appreciate the valley below.

Back in my little loft, the moka pot went on the stove and I’d wait till steaming ceased to enjoy a strong coffee with milk and my now-toasty-warm burek. I’d write a bit, work. Later, a break would mean a walk around the 1,000-year-old city walls, often stopping in awe at the beauty and stillness, and my fortune to be there then. There, I learned that goals becoming reality doesn’t mean they stop feeling like a dream.

Then, home for more work, followed maybe by braised meats for dinner with local bread from the shop, and a quiet night. Some nights I’d grab a substandard pizza at the hilltop konoba, consumed over wine or lavender ice tea as the sun sank behind western peaks. A couple times, I enjoyed true luxury: Polenta and white truffles at Mondo Konoba, across from my apartment. Lauded by Anthony Bourdain on No Reservations, the New York Times said the eatery was “the way old world food is meant to be.”

Some days I’d venture to other hilltowns like Groznjan, or the big city of Trieste, in Italy. Other days I’d take a country drive to find a remote but well-regarded restaurant burrowed into a hillside, impossible to spot until passing by a third time.

These fishermen off the coast of Rovinj are doing what their ancestors have done for thousands of years. A way of life, there is something calming about watching the Adriatic sun sink as these men catch fish for their livelihood.

Short Sojourns: Good for the Soul

Like most well-made plans, many of my expected adventures never came to pass. But then others unplanned became more than I could have hoped. Like my trip to the coast, just an hour away, to amazing Rovinj. As much as I loved Motovun, it had little to do. Rovinj, also largely built by Venetians over the centuries, was built upon a small island adjacent to the Adriatic Coast. It had far fewer hills and far more streets to wander. The ocean fills my heart at any time, and this was certainly true in Rovinj. After a day or two of exploring, Rovinj felt to me like it could be a cross between Venice’s landlocked streets and Sicily.

Two nights planned in Rovinj ended becoming five nights. That’s how much I loved it. Off-season, the town was closed for business for the most part, so I wandered streets alone. Few restaurants to choose from, but I didn’t mind that at all. I was there to drink espressos and stare out at the Adriatic, where generations of fishermen supported themselves, their families, and communities.

A friend was made, and we spent some time together before she left for Italian adventures. Another night, only myself a table of Italians were in a fine restaurant. The Italian party’s leading provocateur kept bringing me glasses of wine, describing what I should expect. A winemaker from Bassano del Grappa, he’d wave his hand with a flourish and say “Buen provecho!” and leave me to it. I felt as if I’d truly arrived in Europe.

I have dozens of photos of this arena from that day but this one does a good job of conveying the emptiness. What a thing to experience.

Falling into History

At the end of my week, I spent a day in Pula, on the southernmost tip of Istria. Once a critical trading port for the Romans, Pula remains rich in Roman ruins, with excavations ongoing. Included in that is its Roman Arena, one of six remaining on Earth. It’s not the largest arena in the former Roman Empire – that’s Rome’s Coliseum – but it is in the best condition.

Visiting the arena, I became a life-long fan of off-season travel.

You see, on that cold November day, I found myself alone in that 2,000-year-old arena. Almost alone, anyhow. There was a security guard, two restoration workers, and myself. The paid staff stayed behind the scenes, likely realizing how profound an experience it was for me.

I’d like to tell you how that feels but the words don’t exist. Trembling, I knew few people in history have probably ever had stood solo on the floor of that particular arena.

This shot shows the size of this arena, and how close it is to the sea — important, since this was a major trading hub and visitors would want to be entertained. On the right, that is not new construction; that’s how clean they’re getting the old stones. The security guard told me that’s all original, that none of the arena has needed to be rebuilt.

Alone in Roman Ruins

Walking alone in the stony holds beneath the arena, my footsteps echoing in the low light, hair stood on my arms. There, gladiators once paced and brooded before being thrown into the arena against each other or even against fantastic beasts, like tigers. Christians would have cowered in chains, fear pounding in their hearts before being sent into their certain ends. Those deaths were foreshadowed by screaming cruel spectators, roaring for bloodsport, all while the Christians shivered in wait for their moment to come.

I was there for 2.5 hours, alone, not because all that time was needed to see it, but because I understood how incredibly fortunate I was to be there by myself.

No noise, no crowds, no lines, no crying, no yammering kids, no shoving tourists. Nothing but me, ancient ghosts, and a pale winter sun casting long shadows on the sand.

When not distracted by human variables, there’s a haunting, eerie vibe in a place like that. We think of movies like Gladiator when we call to mind places like Coliseums, but that really happened. It’s not only a Ridley Scott fiction. Gladiators were real. People got devoured by beasts while crowds roared and demanded death for amusement. Swords and spears clanged against armor, ringing out over bloodthirsty throngs hollering for more. Emperors and senators decreed who should live or die. Blood stained the sand while slaves lost their lives for entertainment.

And I stood there, on the arena floor where blood-devouring beasts growled, lives ended, and champions heard their name ring out.

I almost threw my arms up and shouted “Are you not entertained?” in a nod to Maximus and Gladiator. But reverence for the moment prevented me. I didn’t need to shout. For that moment, I owned an arena. Me, alone.

For more than two hours, strolling the stands, as wind howled, I shot photos. Awe struck me — this was the life I opted into. How many more jaw-dropping experiences like this would await me?

Homeward Bound

I saw more ruins that day, but nothing that moved me or awed me like that arena.

After a long, slow dinner and a sunset over the Adriatic, I drove the winding dark roads back to Rovinj for one last night. Ambling slowly along seaside cobblestones after parking my car, I fell into thought. I fought back tears. For a rare moment I realized this was only the beginning of “I, Nomad” life.

When travelling alone in the off-season, it’s easy to be found by quiet, still moments of spectacular gratitude. Sometimes gratefulness roars at a fever pitch. It chokes the throat, makes eyes well up, and words catch… sometimes for days or months. Maybe this is why it’s taken me six or eight tries to write about Istria in a way that could convey to you how much it moved me.

Rovinj was as profound as any five days in my life have been. But then there was Motovun, too, and it wasn’t an also-ran… not by any stretch.

Sometime change comes in ways we can’t process or understand until weeks or months or even years later. It’s been nine months since that day on hallowed sand in that arena. Nine months since I caught an Air France flight to Portugal and culture-shocked myself into a new phase of mind.

Istria, for me, is a place where magic lives. History comes alive, legends roar on the wind, and ruins speak loudly. Istria is one of many places a piece of my heart remains.

Dig this post? Pin in!

-

[…] Istria’s shortcoming is that it doesn’t realize how incredible it is. – Steffani Cameron […]

Leave a Comment

Awesome! I believe that some of the reasons I love Europe are present in this account. Almost unspoken and undeniably ancient; places that have seen so many upheavals, catastrophes, and different peoples; monarchs and paupers; and the drum of lives both interesting and downright ordinary. It’s the centuries of existence that resonate. You give me an urgency to return yet again.

You’ll get there soon enough, Julie. 🙂 Thank you for your kind words!

Thank you Steffani!

My husband was born in Istria and it was my introduction to Europe at the tender age of 50. We go there every year. I adore Croatia and I am learning more and more about it. I love your sum up of the history. Hope to read more of your writings. Janet R.

Oh, you’re lucky to visit annually! Thank you for your comment. 🙂