When my life as a nomad began, I had been on one overseas adventure. Age 17, England, with my mother and brother.

So, when I went nomad, I’d never travelled anywhere with foreign languages, and certainly nowhere with poverty.

Just crossing the ocean gave me that “Toto, we’re not in Kansas anymore” sense of otherworld immersion. From wandering rural Croatia to dreading whatever mystery meat I might’ve just ordered in Portugal through to navigating cultural differences in Morocco, everything was new to me.

One nation after another has been baby steps. Languages, traditions, scenery – everything new, everything a learning curve.

Sometimes, I just want things to be easy. But that defeats the purpose, doesn’t it?

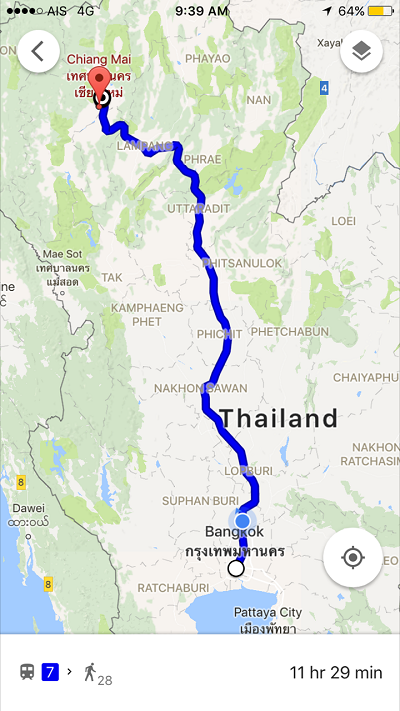

Bangkok to Chiang Mai by Train

I’m writing now in what’s probably one of the biggest cultural learning curves I’ve had yet, by train through Thailand. We’re riding the Bangkok-to-Chiang Mai number 7 express train. It departed Hua Lumphong at 8:30am and should get me to Chiang by 8ish tonight.

I’m writing now in what’s probably one of the biggest cultural learning curves I’ve had yet, by train through Thailand. We’re riding the Bangkok-to-Chiang Mai number 7 express train. It departed Hua Lumphong at 8:30am and should get me to Chiang by 8ish tonight.

This train trip is, in a way, a reckoning with all things nomadic for me.

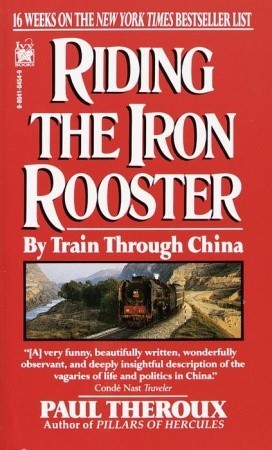

My first ever desire to travel came at age 15, when I read Paul Theroux’s Riding the Iron Rooster: By Train Through China. It would be the first of many Paul Theroux books I would read.

Theroux: New Words, New Worlds

I remember the day I got into Theroux. I was 15, the dog days of summer, lying on my front lawn, completely immersed. It was the first time a book ever really took me somewhere new. Friends found that in sci-fi/fantasy, but, for me, it was in Theroux’s travel I became transported.

Some have followed my writing journey for a time now, and maybe you can read the moments where it’s clear that Hunter S. Thompson influenced me, but my premiere writing influence was always Paul Theroux.

More importantly, he influenced my life choices, my opinions, and my dreams. He’s a curmudgeon and an arrogant bastard, but he’s earned it. When people ask about the dinner party you’d throw, anyone living or dead, who’d you invite? Theroux. Always Theroux. Mata Hari too. The rest of my list fluctuates.

Theroux, for the uninitiated, is probably the only English-language writer whose body of work, in size and scope, competes with Stephen King’s. I think Theroux’s around 55 books now, over 20 travel books, and none are unreadable. He writes fiction, yes, but is mainly known for his epic – and that’s an actual good, non-hyperbolic use of the word “epic” – adventures.

Photo by Steve McCurry, Theroux at work/play.

He’s the kinda traveller who decides he wants to see the Mediterranean, so he creates a travel itinerary to circumnavigate the shores of the Mediterranean from the Rock of Gibraltar around the whole sea’s perimeter, through to Morocco.

But Theroux is never more comfortable than on a train. From the Orient Express to the Turkish Grand Railway Bazaar and riding the Patagonian Express and the Iron Rooster through China, Theroux consumes countries through train windows, choosing stops wisely for immersing himself in their world.

He holds disdain for tourists who parachute into countries without learning anything about the people, the culture, or history. He loathes Sandwich Tourists, the people who travel halfway around the world to eat nothing but the same sandwiches they would at home. He shuns ruins and looks instead for places inhabited by writers, devouring books written in the region or of the region.

Trains and Rites of Passage

From Bangkok to Chiang Mai by Train, the Google Maps version.

From age 15, I always wanted to be as tough and well-travelled and voyeuristic as Paul Theroux in adulthood, but life got in the way and I grew complacent, being content to just endure and survive, rather than push the envelope on my comfort.

There’s a quote from the much-loathed Ayn Rand that I glommed onto in my youth then failed to live by, something like, “Avoiding death does not equal living life.” For years, I simply avoided death.

And so today I’m on a train in Thailand. Today, I’m crossing the landscape from a comfortable traveller to someone having a different experience. I could’ve taken an hour flight for barely more than I paid for this train, but then I wouldn’t have seen all this.

I’ve so far seen families of four riding scooters through flooded plains, water buffalo, palm trees, high mountain temples, the world’s largest golden Buddha, the 800-year-old ruins of Phra Prang Sam Yod where monkeys scurried about, and more.

To See the World is to Know it Better

Midway through, going from Bangkok to Chiang Mai by train, the train tracks are raised. Fields both sides of us have vanished underwater. It’s been newly-formed lakes for maybe 10 or 20 kilometres. Water is sometimes as high as the roofs of the abandoned houses surrounded in these fields. There’s supposed to be a river near here but all I see are wide, relentless waters on both sides, trees jutting out here and there, as if to say “This isn’t what you think it is.”

I’m left peering through my window, wondering about climate change and how it will affect entire regions. Floodwater like this can’t just evaporate overnight, can it? Is this the birth of new freshwater lakes? Is this how it happens, one rainfall after another? Could this be the start of landscape changing to the point of no return? Will all this farmland be lost to a vengeful Mother Earth?

Will this train track, spanning hundreds of kilometres, a lifeline for millions of Thais, be forced to reroute to higher pastures? If its fields and agricultural land is lost to newfound lakes, then what will that do to this small country, which is 1/20th the size of Canada, but with double our population? And worse yet, what does it do for the air quality of such a populated region when a carbon sink like this is transformed to lost to water?

Phichit, Thailand, houses on stilts over the River Choi aka Huai Choi, halfway to Chiang Mai.

The Tricky Nature of Timing

A quote is often wrongly attributed to Buddha or the Dalai Lama, but was said by self-help author Jack Canfield: The trouble is, you think you have time.

It’s part of the impetus for why I felt I had to sacrifice everything and cram my life into a bag, taking to the road for a life unwritten, unplotted, and unknown.

Part of what I stopped thinking I had time for were the changes being brought about by climate and politics. Turkey, for instance, is a country I no longer feel I can visit, thanks to its crackdown on writers. Myanmar is another that’s recently been struck from my list. Those opportunities are lost… for now. But time doesn’t stand still and those opportunities will one day return again.

The more I travel, the more I realize how little we take for granted. I do this less often, now. Whether it’s that I’ve walked over a bridge where, one morning in April, 1992, a sniper killed two Sarajevans having a stroll, which started a four-year war, or it’s just in my riding this elevated train through flood plains, I’ve learned how fleeting moments in time are. History is forever renewing itself and adding pages to its story.

Watching the World Roll By

Lunch on the train from Bangkok to Chiang Mai. If you’re thinking airplane food looks glamorous compared to rice, “fried spicy mackerels” and “crispy fried chicken” (which was not at all crispy), then yes. But hey, man, when in… Thailand, right? And lest you be WOOED by said lunch, be forewarned, you have to spend the big bucks for second class on the air-conditioned #7 train to get this upscale fare.

The flood plains have ended now. The landscape has changed little. Palms, and other trees of all kinds. The odd river or tributary blinks past, always with Thais under umbrellas, fishing on the banks. There are fewer temples than there were. What copses of trees we come across now are thicker, richer, taller. Rainclouds gather in the north while a scorching sun streams in through my window. The locals, probably inured to the scenery, have all closed their dirt-stained, age-betraying, once-beautiful, Tiffany-blue poly-sateen drapes. But me, the fat white farang girl clacking away on her laptop is the only one silly enough to sit in hot sun while ironic air conditioning periodically breathes on her neck.

But it’s so pretty, I think.

We just blew past a small temple, probably no more than 30 could fit inside, but it is resplendent in gold and peaches and pinks and reds, with the trademark Thai peaked roof jutting some thirty feet in the air. Buddha gets a lavish temple even here in the poor rural provinces.

Then came the rust-brown, silt-rich Nan River, which has been near us ever since Bangkok’s Chao Phraya split into the Ping and the Nan. The Nan meanders near us for what looks like another 25 or 30 kilometres, then winds eastward until it peters out near Lake Sirikit, just outside of Laos.

Around when the Nan takes its leave of us is when Google Maps suggests the terrain finally gets serious.

Here, There, Same-Same, But Different

The last time I saw such a red river was this past February, when we went into Agadir, Morocco, to shop the Wednesday souk for fruit, vegetables, olives, and nuts. The river had been nearly non-existent days before but the torrents that had fallen brought the sands of the Sahara right down to the coast, bleeding rust red into the Atlantic Ocean.

The dirt roads here have the tinge of red-brown that I’ve seen in places like Prince Edward Island and Croatia, lands with great agriculture. I’m not sure what all they grow nearby, but the trip may yet reveal it. Google tells me these forests of Uttaradit were once filled with teak, the wood favoured for mid-century modern Danish furniture. Today, not so much. Like much in our recent past, the teak trees were overharvested. Today, tall lush grasses grow, with paths trampled through by farmers. My first rice paddies. At last.

Uttaradit borders Laos, which excites me, for it means I’m moving toward more and more exotic territory. It’s taken 6 hours to come 490 kilometres, but the final 240 kilometres will take the same amount of time – another reason for my ever-increasing excitement. What kind of landscape looms?

Strange Sights from Bangkok to Chiang Mai by Train

It’s second class by train from Bangkok to Chiang Mai, baby. Air-conditioned, which, BELIEVE ME, you WANT TO PAY FOR. “Feels like 40” for 12 hours is not a thing you EVER need to experience in a train car where it’s actually hotter.

Rumbling north, the foliage grows thicker and thicker. It calls to mind the forests and jungles of every Vietnam War movie I’ve ever seen. Part of me has yearned to see these things.

We’ve just passed the first children’s play park I’ve seen anywhere on my Thai travels, complete with statues of a triceratops and T-Rex. It’s weird little things like that which remind me how alike we all are. Of course Thai kids like T-Rex. Why wouldn’t they? Geography, smography.

And now the capital, Uttaradit. Its train station is half for functioning transport, but the other half is a train graveyard, rusted skeletons linked car after car after car on multiple tracks. Some with bushes growing out of them. A fortune could be made if they were smeltered, I’d wager.

With that, we’re rolling north again. The conductors changed over, which is reassuring, if it is indeed such twisting, turning, elevated travel ahead that our speed gets reduced by half.

A whistle blast and away we go, another small station, and on to the mountains. Terrain maps tell me we’re just 15 minutes from what I really want, the jungle and highlands. This region appears more affluent, as I’m noticing street lights periodically. To the right, across the aisle and out the window, I see my first rolling and pyramid-shaped mountains in the distance. And here we go.

Rumbling in the Jungle

I’m quickly stunned by verdant richness. Suddenly, myriad plants and trees of all kinds. Foliage so dense no light pierces it. Ground? What ground? The train slows. Gapingly beautiful, everywhere, everything. Pan Tong Phueng is the first mountain town we’re stopping in, and now things get real… real fast.

Where there are mountains, storms linger in wait, and here we seem on the cusp of northern monsoons. Monsoon? Meh, I won’t mind at all.

I’m always amazed how little things can connect me from one place to another. Red, red earth. Tones of the Cameron family home, the same dirt all over Prince Edward Island. Potato heaven. Agriculturally-rich, as this relentlessly thick jungle proves. Now and then I see a wooden bridge, maybe a shack, and they’re so perfectly picturesque, fitting into the scenery of every jungle movie I’ve ever seen. I always imagined such rustic cinematic touches to be a little over-the-top, but they turn out to be perfect.

When Arrival is a Departure: Chiang Mai At Last

I became lost in the dwindling daylight and the jungle scenery while the tracks clacked away for another two hours as the sun set and a monsoon greted us south of Chiang Mai.

Getting into town proved a frustrating turn in my evening – a messed-up reservation, a frustrating banking experience, an underwhelming substitute lodging, a cheating tuktuk driver. But eventually I fell asleep and morning came.

I loved a song in 1988 that came to mind as today’s dawn settled in and my attitude righted itself. I turned my thoughts toward being excited to be in a new place, even if I don’t have the time to explore it today.

If the lonely night surrounds you

Yeah, you’re weighed down by gloom

No, you don’t like how it feels

In your dark and dirty room

It’ll be easier in the morning

It’ll be easier in the day

Sun will shine on through your window

We got light to lead the way

(Hothouse Flowers, It’ll Be Easier in the Morning)

And that’s that, the train from Bankok to Chiang Mai did, in fact, reach Chiang Mai! YAY!

And, yeah, it was easier this morning.

As the years bleed away and memories grow hazy, what’ll still be in my mind is that train ride. The dirty city outskirts, then endless fields leading to flooded plains, the dotting of unexpected small mountains barely hinting of what was to come, then the slow thickening of foliage, the taller trees, the gradual terrain shift, then the mountains covered in red earth and jungles, followed by the dark of night and a monsoon battering the speeding train as we hurled over the final tracks to Chiang Mai.

Something small and intangible changed in me as both a writer and a traveller yesterday. I know it, but I don’t know how it’ll play out. But somehow, it mattered. Something changed.

And that’s all I need to know, right?

Travel has its ups and its downs. The bad times’ll come, but then the morning will too. Sleep it off, shake it out, and move the hell on. That’s all we can do, just like in life. Lessons learned travelling from Bangkok to Chiang Mai — all for the low, low price of $70.

Whatcha Need To Know: Trains to Chiang Mai run daily. I bought my ticket through 12Go Asia, who proved to have awesome service in letting me know via email the night before my departure that my train occurred before their opening hours and I’d need to fetch my tickets from their security guard. Worked like a charm. I didn’t realize I’d get lunch, and I had no choice in what I got, so if you’re vegetarian or celiac, bring your own. Nothing can be bought on the train, as far as my experience went, and there’s no time nor opportunity to buy from the station. Get the air-conditioned trains. Check Seat 61 for more information. But subjecting yourself to that brutal heat and humidity for 12 hours to save a few dollars would be beyond foolish.